“When the public grows tired of the gimmickry and non-wrestling oriented shows the WWF promotes, the AWA will emerge again,” said Verne Gagne to me in 1991.

Verne Gagne was the owner of the AWA, one of WWF’s fiercest competitors in the mid-80s, and when I spoke to him in 1991, he had only very recently stopped promoting wrestling shows.

The AWA was last major opposition to fall to WWF in the ‘80s wrestling war, outlasting Jim Crockett, Jr. and the NWA by three years.

By 1991, though, the wrestling war itself had been over for several years, and AWA had been in a downfall for about the same amount of time.

I tracked Verne down by mailing a letter to his last known office address on a whim and requesting a telephone interview. I told him in the letter that I wanted to write a story about him for a newsstand pro wrestling magazine.

He responded quickly to my letter, to my delight.

The tone of Verne’s voice when we spoke was friendly, firm and confident. It was clear to me from what he said that he believed WWF’s “gimmick-oriented wrestling shows”, as he referred to them several times, were just a fad.

Traditional pro wrestling, as he knew it, built around quality in-ring work and feud-based storytelling, would have a comeback, and soon. WWF, and the “gimmickry” associated with it, would fade away as fads do.

These were Verne Gagne’s steadfast beliefs.

““I appreciate the support wrestling fans have given me since I broke into wrestling,” said Verne. “This is a great, great sport and I really hate to see it destroyed the way it is today. [Vince] McMahon by using wrestlers that display such poor quality of wrestling in the ring, he makes the sport look bad to the general public.”

In the decades following from when I spoke to him, Verne Gagne would be often depicted by “historians” as being completely out of touch with what the wrestling public wanted and that being the repetitive provided conclusion behind AWA’s demise.

I saw it differently in the moment, and I still do now.

There were many factors that contributed to AWA’s demise that could be explored, and warrant it being done in an in-depth manner in a piece much longer than this post. However, my main takeaway from my conversation with Verne Gagne all those years ago was that Verne was resolute on how he believed pro wrestling should be presented.

Therefore, Verne was unwilling to change his beliefs on that, and how he presented his wrestling promotion, even if it meant the end of the AWA and his time as a wrestling promoter.

He certainly couldn’t have been content exiting from the wrestling business when he did and the way he did, but he accepted it. The wrestling business had been his life and passion for over 40 years.

Verne was strongly opposed to the WWF style of wrestling. He felt that the “cartoon type of characters” were turning away adult fans.

As the WWF became an increasingly more popular and higher profile, Verne said he found that the wrestling audience consisted more and more of younger people that wanted “cartoon images instead of down to earth, solid wrestling action.”

“These [wrestlers in the WWF] come out and say ‘Here is my body. I’m wonderful. Look at my big muscles’. They can’t do anything in the ring but kick, punch and clothesline. These men are not wrestlers,” contended Verne.

How did a pro wrestling promotion go from being in the mid-80s, at the beginning of the pro wrestling boom, known as “one of the big three” in the professional wrestling world, along with WWF (later to be called WWE) and NWA (later to be called WCW), to being extinct within a few years?

Let’s explore.

THE ROOTS OF THE AWA

It was unfathomable to think in 1983 that the AWA would be extinct by 1991. They were packing arenas in the Mid-West on a regular basis and during that decade had featured, at different times, a plethora of top name talent such as Hulk Hogan, Jesse Venture, King Kong Bundy and The Road Warriors to name a few.

The promotion had a rich history dating back to 1960.

The AWA was Verne Gagne’s vision that he made a reality in the aftermath of behind-the-scenes being denied an opportunity to be anointed NWA world champion, the most prestigious title of the time.

In Verne’s storyline version of the formation of the AWA that he recounted to me, the promotion came about because of a dispute among NWA promoters. Like much of pro wrestling, the actual behind-the-scenes account was probably more dramatic and intriguing.

The driving person behind the formation of the AWA, and owner, was Verne Gagne himself from day one (along with his business partner Wally Karbo).

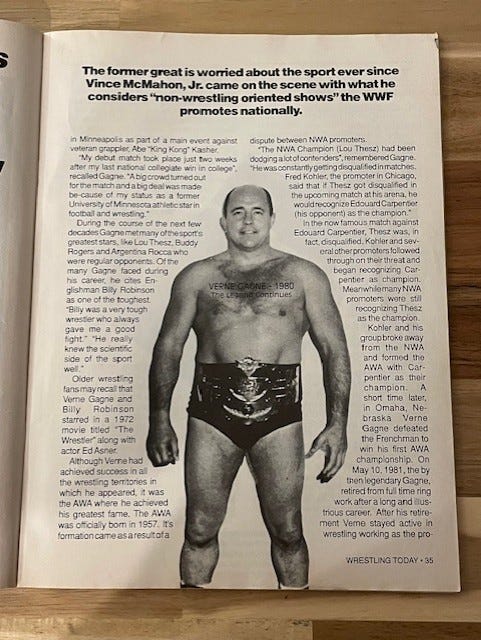

“The NWA champion Lou Thesz had been dodging a lot of contenders, and he was also getting disqualified in a lot of matches. Fred Kohler, the promoter in Chicago, said that if Thesz got disqualified in the upcoming match at Kohler’s arena, he would recognize Edouard Carpentier, his opponent, as the champion, “said Verne, in telling me the “on-screen” story of how AWA was formed.

All magazine interviews with wrestlers and promoters in this era were done in character, with suspension of belief.

In the match against Edouard Carpentier, Verne said Thesz was disqualified. Kohler and several other promoters followed through on their threat and began recognizing Carpentier as champion. Meanwhile, many NWA promoters were still recognizing Thesz as the champion.

Kohler and his group broke away from the NWA and formed the AWA with Carpentier as their champion. A short time later, in Omaha, Nebraska, Verne defeated Carpentier to win his first AWA championship.

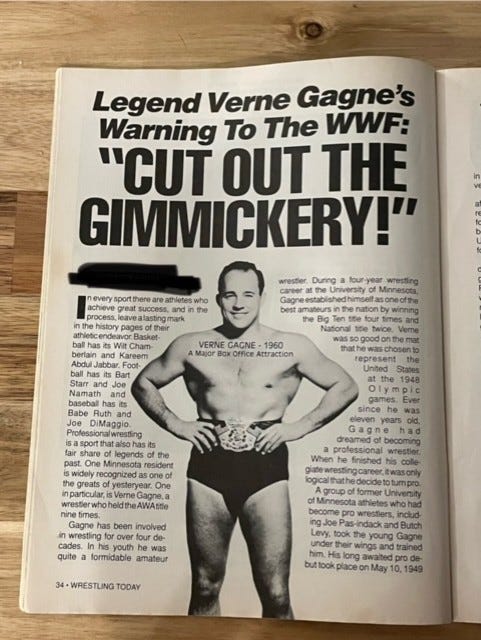

Verne was a passionate athlete who was a formidable amateur wrestler prior to breaking into pro wrestling. During his four years at the University of Minnesota, he established himself as one of the best amateurs in the nation by winning the Big Ten title four times and National title twice.

Verne told me that he had wanted to become a professional wrestler since he was eleven years ago.

When he finished as a collegiate wrestler, it was only logical that he would turn pro, he said. A group of former University of Minnesota athletes who had become pro wrestlers, including Joe Pasindak and Butch Levy, trained Verne Gagne.

His long-awaited pro wrestling debut took place on May 10, 1949, against veteran grappler Abe “King Kong” Cash.

“My debut took place just two weeks after my last national collegiate amateur wrestling win,” recalled Verne. “A big crowd turned out for the match, and a big deal was made because of my status as a former University of Minnesota athletic star in football and amateur wrestling.”

Verne wrestled for the next 32 years and was a 10-time AWA champion by the time he retired in 1981.

VERNE GAGNE THE TEACHER

Verne Gagne trained many people over the years to become pro wrestlers.

His most famous class was in 1972. That year, Ken Patera, The Iron Sheik, Jim Brunzell, and Verne’s son, Greg, all trained in the same class at Verne’s rudimentary “wrestling school”.

A training camp was perhaps a better term for it than a wrestling school. The facilities consisted of a tattered and hard looking ring in an unheated barn. The training program itself constituted a high volume of assorted ultra physically demanding conditioning exercises on the large rural property where the barn was located, as well hours upon hours of wrestling drills in the ring.

Film footage exists of Verne’s training camps in the ‘70s and it has a Rocky Balboa-esque training feel to most of it. That comes from the combination of the crude setting and visible sight of the trainee’s breath in the cold Minnesota air as they are put through the paces both in the ring and out of it.

The man who would become the most famous graduate of that 1972 class was Ric Flair.

Gagne told me in 1991 that Flair’s huge success surprised even him.

“I didn’t think he would go as far as he did,” admitted Gagne.

Flair came to Gagne’s camp after spending two years at the University of Minnesota as a wrestler and football player. He was overweight, carrying 300 lbs. on his frame, remembered Gagne.

“I worked him hard during training and was able to help him bring his weight down,” said Gagne.

Flair had one key ingredient back then that Verne believes helped make him a success in pro wrestling.

“More than anything, I have to say Flair was a dedicated student of professional wrestling,” said Verne. “He was very serious about getting into shape and becoming a good wrestler.”

As the promoter of the AWA, Verne Gagne had many of the ‘80s top stars at one time or another working for him.

Hulk Hogan first caught on with fans in a major way as a good guy while wrestling for Verne.

Wrestling lore has it that Hogan came to AWA after being fired by Vince McMahon, Sr. of the WWWF for playing “Thunder Lips”, a bit part, in Rocky III. So it goes, McMahon Sr. told Hogan if he took the part offered to him by Sylvester Stallone then he would be fired. As it turned out, Hogan’s brief appearance as “Thunder Lips” where he wrestled Rocky in an exhibition wrestler vs boxer match was in many ways the general public’s (i.e. non-wrestling fan) introduction to Hogan.

One could ponder the alternative pro wrestling world that might exist if Vince McMahon, Jr. did not bring Hogan back to the WWF and make him the focal point of the national expansion. What if Hogan had remained in the AWA and Verne Gagne had made him champion over then champion Nick Bockwinkel? What would the pro wrestling world look like today? Would it still be dominated by WWE?

Verne told me that when Hulk Hogan first contacted him for a job in the AWA, he was on the verge of quitting wrestling.

“Hulk called me on the phone,” he recalled. “He told me that he couldn’t make it the way things were going and that if he didn’t get work up here in the AWA, he was ready to quit wrestling.”

According to Verne, it was in the AWA that Hulk Hogan “found himself.”

“We changed him into who he is today [in 1991] by sitting him down and telling him who he was. A light just went on and he started doing good interviews and building up a following,” said Verne.

A PROMOTIONAL WAR IN FOCUS

In 1984, a pro wrestling war raged in the United States.

A Northeastern regional wrestling operation before Vince McMahon purchased the promotion from his father in 1982, the WWF under his ownership rapidly expanded into a national promotion. In the process, they were promoting shows in the existing territories of the regional wrestling promotions across the country that had been entrenched in specific towns for decades.

WWF signed the top talent from various territories and secured the local television slots away from the territory promoters. The territory promotions depended on the local television to promote their live events, which was the core of their business. Then the WWF presented shows in the same towns where the territory promotions promoted, but WWF did it with a star-loaded roster.

The local promotions could not compete, and the crowds for them vastly diminished.

The overall result was the quick collapse of the territorial system with many promotions going out of business in rapid succession of one another.

The WWF presented pro wrestling with flamboyant gimmicks attached to the wrestlers and character development sketches as part of the programming. This was opposed to straightforward pro wrestling like what was traditionally presented based around grudge-based feuds and match-hyping promos on the mic.

Promoters from the old school like Verne Gagne were totally against the WWF’s style of wrestling and Vince McMahon’s expansion tactics.

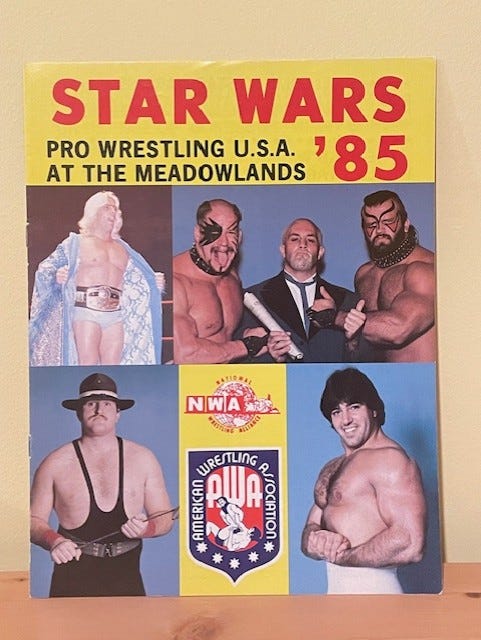

To that end, Pro Wrestling USA was formed in 1984 to prevent McMahon from taking over the wrestling world.

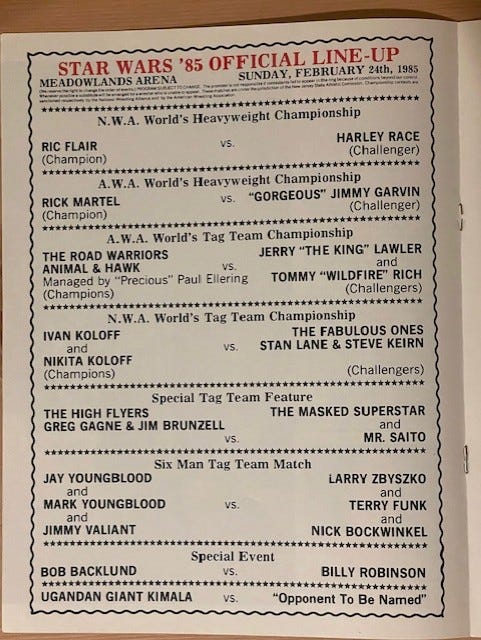

Pro Wrestling USA consisted of several promoters from around the country, the primary ones being Verne Gagne from the AWA and Jim Crockett, Jr. from the NWA, who brought all their talent together to appear on the same shows. The concept sounded great on paper to have the stars of the AWA and NWA appear on the same show and have champions vs champion matches. The consensus of the time was that it might succeed in drawing fans away from the gimmick-oriented WWF and prevent further growth.

The initial Pro Wrestling USA shows were successful. In September 1985, SuperClash was held in Chicago and drew 21,000 people for a double main event of Ric Flair vs Magnum T.A. for the NWA world title and Rick Martel vs Stan Hansen for the AWA world title.

Behind the scenes, though, NWA and AWA were unable to work together and there was talk of continual disagreements over the finishes of the matches. After approximately a year of existence, Pro Wrestling USA disbanded.

The AWA continued to promote shows with an emphasis on holding them mainly in the Mid-West region of the United States.

WWF, though, has succeeded in signing away many of AWA’s bigger names. The best example being Hulk Hogan, who felt the AWA wasn’t using him to his fullest potential because they would not make him the world champion, despite the tremendous crowd responses he was getting at shows.

In 1986, the AWA was still drawing fairly strong crowds with names like Nick Bockwinkel, Rick Martel, Stan Hansen, Curt Hennig, The Rockers, and Sgt Slaughter. However, as the year progressed the crowds began to dimmish, and AWA began promoting less shows. The travel schedule was reduced to mainly TV tapings in Las Vegas for their show that aired on ESPN and regular house shows in Minnesota and Wisconsin.

The AWA was no longer holding shows in 10,000 seat capacity areas, but instead high school gyms.

THE PATH TO THE END

By 1987, rumors began to spread that AWA was heading towards extinction. There was a brief revitalization though with the formation of an alliance with World Class and Memphis Wrestling. However, this alliance proved to be even shorter than Pro Wrestling USA. This time there was a rumored disagreement between AWA and Memphis over payoffs to the Memphis wrestlers, and the entire alliance collapsed.

The AWA schedule was further reduced to mainly focus on Minneapolis/St. Paul and Rochester, Minnesota, and the promotion preserved on.

The AWA made one last attempt to revitalize fan interest when they introduced The Team Challenge concept in the fall of 1989. It was rumored they were on the verge of losing their ESPN television contract (which reportedly accounted for most of their total revenue coming in).

The concept of Team Challenge was three teams with the members competing against each other in assorted stipulation matches and getting points for winning. The prize for winning the tournament was announced as 1 million dollars.

The three teams were “Baron’s Blitzers” captained by Baron Von Raschke, “Larry’s Legends” captained by Larry Zbyszko, and “Sarge’s Snipers” captained by Sgt. Slaughter. Before the tournament reached its conclusion Slaughter left the promotion, and his team was re-named DeBeers’ Diamondcutters with Colonel DeBeers as the captain.

The series featured some notorious matches that did not fit with the traditional pro wrestling AWA had always been associated with. The most infamous, and memorable for the wrong reasons, was perhaps the “Turkey on a pole match” where a raw turkey was put on a pole and to win the match the turkey had to be retrieved.

The tournament was also muddled by the frequent changes of team members.

Further hampering the general atmosphere for the tournament, they held the matches in the latter part of the tournament in an empty room, with pink walls, where the ring filled up much of the room.

It looked very odd on TV, and they provided viewers with the explanation that the “venue” was necessary to prevent outside interference. It was said in the wrestling rumor circles of the time that the odd venue was due to AWA having difficulty drawing crowds and not wanting near empty buildings being shown on TV,

Meanwhile, at this same time in the same town, Minneapolis, Eddie Sharkey’s Pro Wrestling America was consistently outdrawing the AWA for shows where the AWA actually did put tickets on sale. PWA had no television and a roster of mostly local talent from Sharkey’s wrestling school.

Sharkey recounted to me at the time that PWA was consistently drawing approximately 500 people to shows in the Minneapolis/St. Paul area, AWA’s home base. He related that he had heard that AWA was giving away tickets to try to build passable crowds for TV tapings and that AWA wrestlers were going out on the streets of Minneapolis to pass free tickets out, only to have them rejected.

When the Team Challenge Series finally concluded in August 1990, it was also the end of the AWA itself soon after. The final AWA champion was Larry Zbyszko, but he left for WCW after AWA stopped promoting shows in 1990. This was a few months before they officially shut down.

The WWE bought the rights to the AWA name and tape library in 2003. They used the footage to release one DVD with a documentary and “classic” matches not too long after the purchase. AWA footage can currently be found on the WWE Network on Peacock.

In the early 2000s, a promoter started running shows using the AWA name in the heart of the old territory in and around Minnesota. WWE claimed ownership of the AWA name, filed a lawsuit and ultimately won, shutting the promoter down.

Verne Gagne died in 2015.

Some versions of pro wrestling history may tell us AWA was a poor promotion, but I strongly encourage you to seek out AWA shows and matches from the mid-80s, before the promotion went on a downturn, to make your own judgement.

This was the era where I was introduced to AWA, and I tremendously enjoyed watching the promotion’s shows on ESPN as a new wrestling fan back then.

You can subscribe for free to The Pro Wrestling Exuberant to receive all my new posts via email, as well as new episodes of my own podcast, Only The Best Independent Wrestling.

By becoming a free subscriber, you will also be able to access my Substack website to see the full archive of all my pro wrestling posts. This is also where the full archive of my Notes collection is housed. Notes is shortform writing from me on a variety of topics related to pro wrestling, my writing process and writer insights and tips.

If you like my pro wrestling writing, please consider upgrading to a paid subscriber for $5 a month to get exclusive content, like posts about and pictures of wrestling memorabilia from the ‘80s to present from my personal collection, as well as subscriber exclusive audio recording about ‘80s/’90s pro wrestling and original manuscripts, with updated commentary, of pro wrestling magazine articles I wrote in the ‘80s and ‘90s.

What if everything was in the wrong place at the wrong time?

I don't know if there can be any doubt that looking back on the AWA through a modern lens, it is very dry. Perhaps this was the point, and I do think modern wrestling could use a bit less pomp and a bit more reality, but I just don't know if this style was ever going to work in the excessively flashy 1983-1992 (or so) North American cultural period.

Perhaps if the AWA could've made it past 1992, they could've stood some chance to survive, as Verne was correct and the WWF fad did die a very gruesome death, in popularity terms, from 1992 until they truly started changing things in 1996 and 1997, but by then it'd just been a little bit too long. The wrestling landscape had irrevocably changed to favour big business WWF, at the expense of wrestling as a whole. If the WWF fad had died just a little bit sooner (maybe in 1990 or so) who knows where the wrestling business would've ended up, but it all came just a little bit too late to save the AWA.