The Rasta the Voodoo Mon Story

Recollections from a Pro Wrestling Reporter's Notebook, Part I

* This post is the first in a series about pro wrestlers who I interviewed and wrote articles about in the early ‘90s for newsstand wrestling magazines. It includes as part of the narrative the original profile article I wrote, with updated commentary to add some perspective all these years later.

At the time of the interviews, some of the wrestlers were already legends; others would go on to find great success in the years to follow; others would fade from the scene without finding success in the WWF or WCW (the two major wrestling promotions in the early ‘90s).

All the wrestling magazines, back when I wrote for some 30 plus years ago, covered the scene in tune with how it was presented on TV. It was strictly forbidden to stray from that narrative tone and talk about behind-the-scenes information or the “inner-workings” of wrestling, as is commonplace in modern times.

Times change and print wrestling magazines have long been replaced by social media platforms and other digital resources that analyze and breakdown what goes in the ring. There’s also often commentary as part of that on behind-the-scenes information related to the match and “gossip” involving the wrestlers themselves.

(Pro Wrestling Illustrated, which started in 1979, is the only remaining U.S. based wrestling magazine that is still published today.)

The way wrestling was covered as if it was “real” back when I was a magazine writer was an extension of the prior decades. That was a time when the ins and outs of how wrestling matches were constructed, and other behind the scenes info, was considered closely guarded secrets by those who worked in the business.

When re-reading some of my work three decades plus later, I think it often comes off a bit absurd with over-the-top hyperbole full of clichés. However, it read perfectly well at the time it was first done.

Professional wrestling, after all, has always been about suspension of belief and hype regardless of the decade.

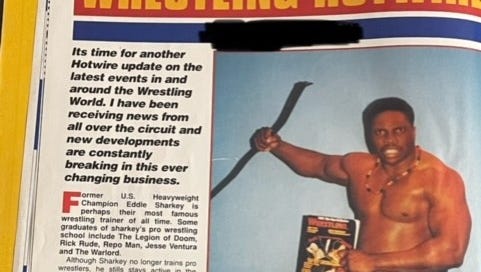

THE LOOK OF A WRESTLING SUPERSTAR, CIRCA EARLY ‘90s

Rasta The Voodoo Mon was the “can’t miss” pro wrestling prospect that did.

Of all the pro wrestlers I met and interviewed in the early ‘90s, none had a better look for television in my opinion than Rasta.

I expected him to become a future WWF superstar and promoted his image heavily in the wresting magazines that I wrote for, including multiple feature articles and numerous excerpts in columns that I wrote.

Nearly all the prospects who I wrote about for magazines made it to the WWE or WCW.

Some were only there for brief periods of time; others achieved moderate success; a select few became huge stars.

Chris Jericho was the biggest success story of them, but the article I wrote about him was never published. The publishing company went out of business right before the issue with the story on “Lionheart” Jericho was scheduled to be printed. (For more on the Chris Jericho article, read my earlier post “Hi, I’m Chris Jericho”.)

Rasta never “made it” in the professional wrestling world.

If you saw him in the early ‘90s, you probably remember him. He was a hard man to forget.

Read on to see how this impressive-looking guy used his disappointment from not finding wrestling fame to evolve and find fame with a much wider audience.

Rasta first came to my attention through appearances on the short-lived UIW television show, which was a local promotion that had a late-night slot on a local TV channel.

You probably have never heard of UIW. I barely remember it except for Rasta and a rather generic magazine story I wrote on the promotion that appeared right after they went out of business.

Said magazine article resulted in a future ECW wrestler, who I had never met before, cornering me in a locker room and screaming at me for writing the story because “the promoter was a piece of (fill in the blank) and I didn’t know (fill in the blank again) and I’m a (fill in blank) for writing the article”.

This was followed by more profanities leading into what my shell-shocked mind interpreted as a threat of bodily harm if I didn’t move quick. Hello, nice to meet you too.

As the wrestler’s cheeks flushed with anger, and I stood silently in front of him, another future ECW wrestler, Axl Rotten, was kind enough to lead him away. That was the last I saw of the angry future television wrestling star.

“Sorry about that,” mumbled the promoter, who was flushed in the face too, and seemed embarrassed about the whole incident.

“Ah, I’ll talk to him,” he said, but the look on his face told me he was uncomfortable being in the same room with the volatile fellow too.

Shortly after I saw Rasta in UIW, the GWF television show started airing on ESPN. He was on many of the initial shows, and it introduced him to a national viewing audience

Rasta was tall and muscular with a chiseled physique (6’7” feet and legit 300 lbs. of solid muscle).

He made an even more imposing impression on me when I saw him in person for the first time at an independent show, as TV did not fully capture just how physically large he was.

I thought to myself, “how can a guy who looks like this possibly not be in WCW or WWF very soon?”

He didn’t need to do a lot in the ring to make a lasting impression, after all.

Shortly after Rasta’s appearance in the GWF, another wrestler debuted in the WWF using the same voodoo gimmick that Rasta had been doing.

The WWF wrestler was dubbed Pappa Shango and pushed right to the top, including a memorable moment where he put a “spell” on The Ultimate Warrior on TV. That same wrestler went on to wrestle under several other names in WWF including Kama and The Godfather.

Somehow Rasta never became a big wrestling star.

This is even more puzzling now in retrospect when you consider the early ‘90s scene.

It was an era where size ruled, and opportunities were abundant for men with big muscles and the bodybuilder look.

As far as I know, Rasta was never even given a try-out or seriously looked at by either WWF or WCW.

By early 1993, during one of our periodic phone conversations, I sensed Rasta was considering dropping the voodoo gimmick or perhaps leaving wrestling altogether. He seemed understandably frustrated by the complete lack of attention that he was getting from the national promotions.

I reiterated my belief in him and that I thought he was destined to become a big wrestling star. He wasn’t so sure. He thought the preference towards super muscular wrestlers was going to shift (and he was right).

The wrestling magazines went out of business one after another during that time. Pro wrestling underwent a severe dip in popularity in the early ‘90s after the wave of excitement over Hulk Hogan (Hulkamania) and the other ‘80s wrestling stars subsided.

I moved in other directions away from the wrestling business too and lost touch with Rasta.

We reconnected in 1995 shortly after I became a pro wrestling referee. Rasta wasn’t wrestling much anymore by then, but he looked even more physically impressive and had significantly larger muscles.

He still had a burning drive to make it big with one of the national wrestling promotions. By this point, he had dropped the Voodoo Mon moniker from his persona and was just going by the name Rasta. He talked about wanting to re-invent his image.

We met at a upscale mall food court, where his size drew quite a few stares from the upper-class suburbanites around us, and I laid out an idea that I had for him (well, both of us).

My plan was to create video footage to be sent to the WCW that would land both of us jobs there.

I would become his “on-camera” valet/manager named Chalmers, speak in an exaggerated fake British accent, and dress in a tuxedo. He would still be known as Rasta but would now wear a tuxedo to the ring as well and play the role of a “refined gentleman” of great wealth.

Rasta liked the idea I had for a change of character for him. I would do most of the talking before his matches about “my employer.” Rasta wanted to find several women to accompany him to the ring as well, all dressed classy, and they would throw rose pedals at his feet as he walked to the ring. We were both hyped.

It was my belief at the time that he would have a better chance getting signed by WCW than WWF. For reasons far too detailed to get into here, at the time the WWF had become less interested in recruiting wrestlers with super muscular physiques.

Rasta and I agreed that we’d be in WCW before long, for sure.

Unfortunately, and for reasons long forgotten, Chalmers and Rasta never came together as a wrestling act and never left the idea stage.

The last time that I saw Rasta was at an independent wrestling show in 1997.

We were supposed to ride together to the show, which was several hours drive away in some remote town.

He never showed up to meet me.

In the days before cell phones, I held out for as long as I could and then made the drive myself as quick as I could. I barely made the call time for “talent”.

I don’t remember what he said when I eventually asked why he never showed up.

We lost touch again after that and, from what I understood from wrestlers in the area, he quietly drifted away from wrestling, like so many others.

During one of our last conversations, he had talked about opening a wrestling school, and he wanted me to train the referee students.

He also wanted to start an independent promotion. I was interested in helping him put it together but, as far as I know, nothing came of the promotion idea he had, and he never started the wrestling school either.

Okay, the Rasta story might have ended here, but it didn’t.

I remembered Rasta’s real name about a decade ago and was curious about what I could find out about him on the internet and why the “big leagues” never gave him a look.

It turns out that I was in for a big surprise. I discovered he achieved the fame he always sought, and was destined for, but in a wholly different medium and in front of a much larger and more mainstream audience.

But first, here is the initial feature article I wrote about him. It was the first article about him ever published in a wrestling magazine. My contemporary commentary is in italics.

It’s essentially a fluff promo piece. It was designed to promote the wrestler with fans and hopefully get attention for him from promoters who read the article.

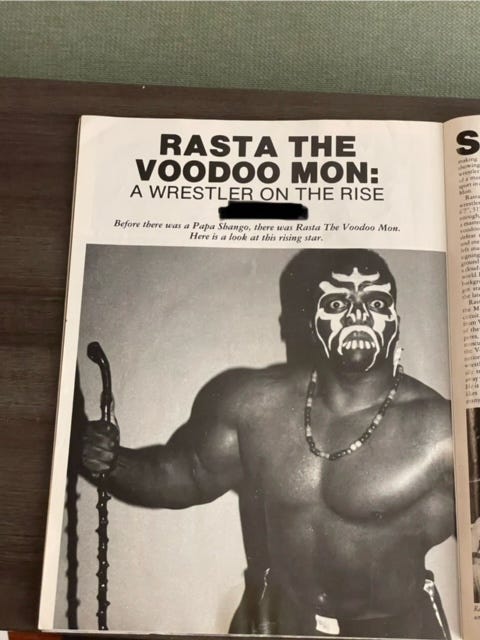

Introducing Rasta The Voodoo Mon

At 6’7” at 315 lbs. of rock-hard muscle, Rasta The Voodoo Mon is a mighty intimidating wrestler. The four-year veteran from Montego Bay, Jamaica intends to inflict pain, discomfort, and generally cripple and maim any opponent that has the guts to step in the ring with him.

**********************

(Just to make it clear, Rasta was not from Jamaica and did not have a Jamaican accent. I don’t recall him ever speaking on the microphone before or after a match. Maybe he used a fake accent if he did, but I doubt it.)

***********************

Rasta has issued an open challenge to wrestlers all over the country and is anxious to show the wrestling world exactly what he can do.

The background of The Voodoo Mon is mysterious to say the least. All that is known in the wrestling world is that he first made his debut in his homeland in 1988.

************************

(So Rasta claimed, as he did our first interview completely in character; it gets better.)

************************

Rasta claims a witch doctor named Dr. Voodoo gave him his start in professional wrestling.

************************

(That was his response when I asked him how he got started in pro wrestling. Why couldn’t he come up with better name for his “witch doctor”? Why couldn’t I for the article? Dr. Voodoo?)

***********************

Fans have to take his word on this because everything else about Rasta is shrouded in secrecy

***********************

(For some reason I always thought Rasta’s real “day job” was working for the U.S. Post Office. Don’t remember why/how I came to that conclusion. Maybe that was a rumor I heard. Maybe someone was joking with me. Hard to recall. One day I asked Rasta or, rather clarified, that he worked for the post office during a casual conversation. He looked at me oddly. “I don’t work for the post office,” he said softly. “Why would you think that?” He never did say what his “day job” happened to be.)

***********************

Besides being a top attraction on the independent scene, The Voodoo Mon also makes appearances in Joe Pedicino’s Global Wrestling Federation and with each subsequent outing he looks more and more impressive. It was in GWF that Rasta was able to show a national television audience his awesome strength and superb physique.

Rasta wrestled for the GWF on their initial shows during the summer of 1991. He accumulated a very impressive record in the upstart promotion, defeating several Texas wrestling veterans like Gary Young and Brian Adias. Fans of the GWF did not know what to make of the Jamaican giant and, as a result, were glued to their seats every time he made an appearance.

Rasta likes to enter the ring with his face fully painted and can usually be counted on to summon some great power from above. The world of professional wrestling had never seen anything like him.

He also claims to be a master of voodoo magic. In fact, in just about every match that Rasta won it can be noted that he pointed at a specific body part of his opponent before the match ended. Later in the match that body part would mysteriously cause pain to his foe. This always allowed Rasta to go in for the kill.

The goals of this up-and-coming young star are quite clear.

“I want to be the best,” proclaims Rasta. “I want to wrestle in the big promotions, against the best talent in the sport, and mark my words, my voodoo magic will beat them all.

On the independent scene Rasta’s number one foe is Neil “The Power” Superior. These two have headlined shows all over the country and have waged some mighty impressive battles. In fact, Neil is one of the few men on the circuit that comes even close to matching Rasta’s raw power.

At the debut show of The Wrestling Independent Network over 1,000 wrestling packed the venue to witness the Voodoo Man work his magic on Neil Superior.

***********************

(This was where I first met Rasta in-person. I approached him about wanting to write a story about him and we did a brief interview from which the quotes and general material for this article came. He was in character once the tape recorder went on, and those are his actual quotes in the article.)

***********************

WIN officials accurately billed the match as “The Battle of The Big Men.” Fans who were hoping to see Rasta’s sadistic style of wrestling were not disappointed as he and Superior gave it their all inside the squared circle.

The heavily muscled physique of this athlete and apparent ease which with he has manhandled many opponents in the past makes it quite clear that he is one wrestler to keep your eye on in the future. The WWF recently introduced a Jamaican Voodoo Man of its own known as Pappa Shango. Beware of these types of blatant rip-offs.

Rasta is the original Voodoo Mon of wrestling, and he is not happy that Pappa Shango copied his style. He is now aching for a chance to face off against this imitator. Perhaps the day will soon come when the two Voodoo men of the wrestling world cross paths.

If it does, rest assured that the sight that follows will not be pretty. Rasta is extremely anxious to prove he is the best Jamaican wrestler to ever set foot inside a U.S. wrestling ring and will stop at nothing to achieve this goal.

Rasta The Voodoo Mon has issued an open challenge to all wrestlers.

“My challenge to any opponent in any promotion has been issued,” stated The Voodoo Mon. “Now it is up to all these so-called tough guys out there to accept it.”

For fans and fellow wrestlers who have not had the pleasure of seeing Rasta yet, he has a stern warning to give you.

“I might pop up anywhere. Don’t trust me, don’t go around me, and don’t try to say anything to me. I can get to you in more ways than one. Rasta The Voodoo Mon has voodoo magic, dolls, power and, most of all, smarts.”

With each win Rasta comes closer to achieving his goal of someday conquering the wrestling world and dealing out punishment to all opponents.

This athlete has the size and look to go far in the sport of wrestling.

Rasta The Voodoo Mon is a young star that could burst onto the national scene anytime soon. For now, though, The Voodoo Mon will have to bide his time and plan his assault on either the WWF or WCW, and possibly even Pappa Shango.

LIFE (AND FAME) AFTER WRESTLING

Rasta, real name Lester Speight, drifted away from wrestling sometime in the late ‘90s to pursue acting. A few years after that a Reebok Super Bowl Commercial where he played a character named “Terry Tate” in 2003 was such a hit that it landed him several high-profile acting jobs.

That followed with a major role in one of the Transformer movies, a reoccurring role on a popular sitcom, and appearances in numerous other movies working alongside big-name actors and for well-known directors.

Search Lester Speight and you may discover you’ve seen him in several television shows and/or movies.

You can subscribe for free to receive all my new posts. If you like my work, please consider upgrading to a paid subscriber to get exclusive content, like posts about and pictures of wrestling memorabilia from the ‘80s to present from my personal collection.

Listen to my two podcasts, The Pro Wrestling Exuberant and Only The Best Independent Wrestling, for free at https://theprowrestlingexuberant.buzzsprout.com.

You can also follow me on twitter/X at https://x.com/tpwexuberant for more original wrestling content.

You're right the name did ring a bell and his name pops up on imdb in a film where he ended up against the Rock. "Faster" is a great film, sure it's a copy of Lady Snowblood/Kill Bill, but it stands out as one of those oddities where Dwane isn't being the same character he always is in films.

Also, Neil Superior... That's a story with a really crazy ending.

As always I absolutely love your post. It's super cool to find someone who is as in love with the pro wrestling business as I am and reading your stories always brings a smile to my face. It also pushes me into thinking about what I could do with my own career in the wrestling business as I did work as a referee. Keep these coming and keep up the great work.