I first started writing about professional wrestling in the ‘80s when I began publishing a mail-order wrestling newsletter.

Pro wrestling newsletters were quite common in those days, and several of the newsstand magazines had columns where they would list descriptions of different newsletters with subscription costs and give the address where to send checks to subscribe. In those pre-internet days, that was the primary means by which I gained subscribers in addition to getting other newsletters to mention my publication in exchange for me doing the same. Often, we’d write guest columns for each other too as another form of cross promotion.

My pro wrestling newsletter’s content consisted of me writing my opinions of different stuff that was happening on TV. There were no live pro wrestling TV shows in those days. Everything was pre-taped, sometimes weeks in advance of when it aired, so it often took quite a bit of time for certain news to reach fans.

My newsletter focused primarily on WWF and NWA, but cable was new and through that I had access to other promotions like AWA and World Class, so I covered them too.

When I was able to, I’d interview a pro wrestler and put that in the newsletter too as either a Q & A piece or a profile article.

I had no contacts at all in the wrestling business when I started writing the newsletter, so initially how I got these wrestlers for interviews was to get in touch with them through wrestling schools.

The wrestling magazines would have advertisements for the schools, and I’d just call the school phone number and ask to speak to the owner, who was always some former pro wrestler of note.

The very first pro wrestler I interviewed was Johnny Rodz, who had been in WWE (WWWF then) in the ‘70s and into the early ‘80s.

He had one of the early wrestling schools in the U.S. and ran it out Gleason’s Gym in Brooklyn, New York. Rodz still has the school and trains wrestlers. Back then, I just called him on the phone and told him who was and what I wanted to do. He was nice enough to do an interview with me on the phone. I don’t think this would have worked so easily nowadays to get a pro wrestler on the phone and for them to agree to do an interview on the spot.

Another pro wrestler I interviewed that same way was Tony Altimore, who wrestled in The Sicilians tag team with Lou Albano in the ‘60s.

I built a lot of contacts in the wrestling business quickly. Whenever I'd do an interview with somebody, I'd always mail them a copy of what I wrote about them and ask if they knew other wrestlers that might be interested in being interviewed and having me write about them.

I eventually started sending my newsletter to wrestling magazine editors and pitched them in a cover letter to have me write a news column. A few answered me and gave me writing assignments, and that’s how I transitioned into writing for wrestling magazines back then.

From the early days of writing for newsletters and magazines, I always enjoyed writing about rising stars.

Most of the wrestling magazine editors gave me a lot of leeway to choose my own topics to write about and frequently allowed me to write features on non-WWE and WCW names and showcase these newcomers with multi-page articles.

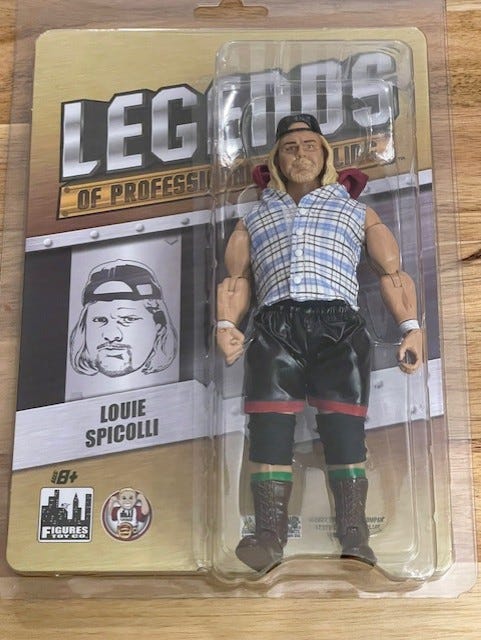

Louie Spicolli was the up-and-coming wrestler I wrote the most articles about in magazines.

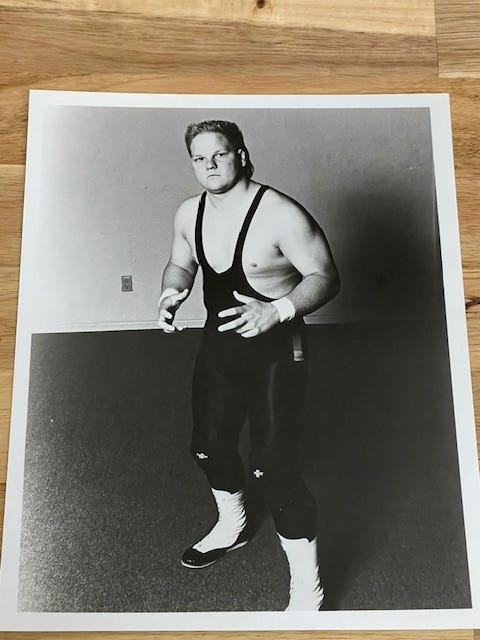

When I first met Louie Spicolli in the late ‘80s, he was in his late teens and had already been wrestling for a year in independent promotions. He wrestled primarily on the west coast and he was doing work in Mexico under a mask as part of a trios tag team called The Mercenaries.

He had also wrestled several matches on WWF TV as a “jobber”. In those days, the wrestling shows did not feature competitive matches for the most part. Instead, the matches largely consisted of a star wrestler quickly defeating a wrestler who was not a name. It was always a one-sided match (called a “squash” in wrestling lingo).

The first time I saw Louie Spicolli wrestle outside WWF, on a tape somebody gave me of him working in Mexico as one of the Mercenaries, I thought he had tremendous potential and given the opportunity would become a star in one of the national promotions by his early ‘20s.

Once I got to know him personally, I took a liking to him with his laid-back personality. We got along well and spoke frequently on the phone about different topics related to pro wrestling, as well as his most recent matches.

The following narrative is largely based on conversations I had with Louie Spicolli beginning in the late ‘80s and through the mid-90s.

- Russell Franklin

1988, Southern California

A group of men hoping to become professional wrestlers gather around the training ring, intently digesting every word uttered by the instructor Bill Anderson.

Hope is big among the trainees. Professional wrestling’s popularity has been on a fast rise since the middle of the decade.

Names like Hulk Hogan, Roddy Piper and The Junkyard Dog have helped pro wrestling gain mainstream recognition over the last several years. Many of the trainees here were spurned to get into wrestling by the lure of the big money that would surely come with being a World Wrestling Federation superstar.

Anderson knows many people answer the call, but only a few have the desire, heart and skill to ever make it to the national circuit. An active wrestler himself for over a decade, Anderson has seen a lot of men enter pro wrestling with big goals, only to quit a short time later when fame didn’t come quickly. Patience and self-confidence are two of the most important ingredients aspiring wrestlers must have, and this is something Anderson has always stressed to his students.

Anderson climbs to the top turnbuckle, balances himself, and then performs a dropkick. The group is clearly impressed by the demonstration. The instructor explains the mechanics of the move and then, asks, “Do I have any volunteers who want to try it?

He scans his eyes around the room. Only one hand is raised. It’s always the same guy that tries the moves first, says Anderson to himself.

The instructor nods his to the student. The young man enters the ring and proceed to perform the move with expert precision.

“Very good,” says Anderson.

He knows this young man, who recently turned 18 years old, is going to be something special someday in pro wrestling.

Anderson’s teenage pupil will prove him right.

Seven years later Louie Spicolli, the student, will be in the WWF.

TRAVELING THE CIRCUIT

Louie Spicolli made his professional wrestling debut in 1988 and in the early days of his career wrestled many times for WWF TV, going against such top names as Bad News Brown, Big Bossman and One Man Gang.

It was a great learning experience for him, he had remarked to me in reflection when we first spoke. He felt by working with name wrestlers, he couldn’t help but get better himself.

He was so good in fact at “jobbing” to the stars on TV that many of them began to request him for their matches. However, several veteran wrestlers advised him from continuing to take such bookings. They explained to him that if he got exposed on TV in that role for too long it would hurt his long-term opportunities to be brought into the WWF in the role of a star.

So Spicolli heeded the advice and focused entirely on wrestling on the fledging West Coast independent scene and nearby Mexico. It was here where he continued to hone his skills in small towns in front of small crowds, wowing audiences with his presentation. He often used the dropkick off the rope as his finishing move.

Spicolli reflected at the time that he never tried to pattern his style after one particular wrestler. Rather, he incorporated a wide variety of styles when he wrestled. Sometimes he would brawl, he said, but other times he focused on suplexes and mat holds. He told me he learned to read the crowds, sensing what they might want to see, and he would adjust his style accordingly in the ring as he went.

Louie predicted future greatness for himself. It wasn’t in an arrogant manner. He simply believed it was his destiny to one day be a star in either WWF or WCW. It was the same necessary self-confidence I saw in another young wrestler during this same time period, The Lightning Kid, who went on to find major stardom in WWF as X-Pac later in the decade.

Fans on the independent circuit began to increasingly believe in Louie Spicolli as well.

“I’ve never had a problem with confidence,” commented Louie to me, when discussing the mental elements necessary to succeed as a wrestler at the highest level. “Yet, I know there is always more to learn.”

Spicolli explained to me that he studied tapes of his own matches to better himself.

“I watch them over and over again,” he said. “I analyze what I’m doing right and what I’m doing wrong.”

He said that most talented young wrestlers, from his observation, didn’t believe in themselves and their ability to achieve greatness, so they didn’t aspire to lofty goals.

“When I was first starting out, I use to look at guys that had been wrestling for five or six years and in WWF or WCW and think, ‘Hey, I can hang with them in the ring.’ I needed to have that mentality.”

A year after his debut, Louie’s work on the independent circuit caught the attention of promoters in Alabama in the dying days of the territory system.

In the decades prior, the territory system had consisted of thriving wrestling promotions in each region of the county. Each promotion had a regional TV show and a weekly touring circuit of mostly small towns along with a roster of full-time wrestlers. Some of these promotions swapped talent with each other, and there was an unofficial agreement to not run shows in each other’s areas.

Spicolli spent two months in the CWF and was paired with veteran wrestler Tom Pritchard as a tag team. They worked an extended program against former NWA star Bobby Fulton and his younger brother Jackie. It was a great learning experience for Spicolli, he told me later, and it served as a springboard to a higher profile promotion.

REBRANDING #1

In 1990 word began to spread in the wrestling world that there was a new promotion about to launch that had secured a national television deal.

There was eager anticipation for a new wrestling promotion in the wake of the virtual collapse of the territory wrestling system and as a result a severely reduced number of pro wrestlers working full-time in the U.S.

The promotion was called UWF and got a weekly television slot on SportsChannel America. Thus, it launched with immediate visibility and hype.

At the initial set of tapings in the fall of 1990 there were several former WWF stars from the ‘80s appearing, including B.Brian Blair, Paul Orndorf, Bob Orton, Jr. and Don Muraco. Additionally, UWF had several newer wrestlers on their roster that they intended to build as homegrown stars.

Louie Spicolli was one of these newer wrestlers on the roster being showcased on the initial TV episodes.

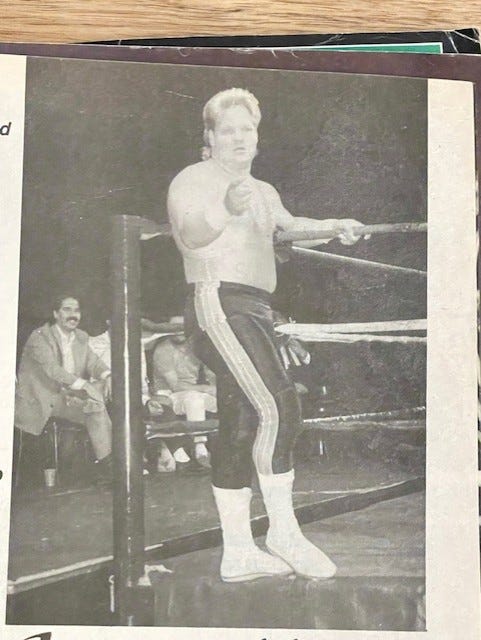

Dubbed “Cutie Pie” Louie Spicolli, he embraced the role of a cocky, self-absorbed rising star and proclaimed himself “the world’s cutest man” whenever speaking on the mic.

Albeit brief, it was a solid national introduction for Louie Spicolli both in terms of his outstanding in-ring work and also his strong ability to speak on the microphone. The promotion itself floundered, reducing its match schedule quickly and losing the Sports Channel America deal after the first year. The promotion was done soon after, but Spicollli’s short time there was hugely significant in his career trajectory.

The national platform helped him achieve his goal of capturing the attention of the WWF and allowed them to see past his early experiences there as a “jobber” and look at him from a different perspective.

It would still be some time though before they finally brought him in.

The next few years were spent wresting in a wide variety of places, including time in the FMW promotion in Japan and AAA promotion in Mexico (where he wrestled under the name Madonna’s Boyfriend).

It would be a match in Mexico for the AAA promotion in late 1994, teaming with Eddie Guerrero, Konnan, and Art Barr as Los Gringo’s Locos, that led to WWF finally signing Spicolli.

Said match took place at When Worlds Collide PPV, and Spicolli’s performance got strong reviews and directly led to WWF bringing him in, he said.

ENTER RAD RADFORD

Several new faces burst onto the WWF scene in 1995.

The promotion was anxious to sign new talent who were capable in the ring and could deliver on a nightly basis.

The WWF was still trying to find its footing to recapture the glory of the ‘80s Hulk Hogan era in terms of popularity with the general public. They were still a few years away from “Stone Cold” Steve Austin and The Rock era which relaunched the promotion into an upward trajectory that continues to this day.

Spicolli became a member of the promotion’s “New Generation” era in the late spring of 1995.

He was re-named Rad Radford with the sparsely developed gimmick he was into grunge music. This was not much to the character beyond his attire and entrance theme music, and he did not receive any video package introduction as was standard in that era in the weeks before a new “character” debuted on TV.

Spicolli was put in a storyline where he aspired to be a member of The Bodydonnas, which consisted of Chris Candio (as “Skip’) and Sunny doing a gimmick as fitness fanatics.

Here’s an excerpt I wrote about it in a wrestling magazine in the mid-90s. Note that at the time all writing in wrestling magazines was done in a narrative voice that was the same as the commentating on TV (to use wrestling lingo, written in “kayfabe”).

“During his first few months in the WWF, Rad quietly went about his business, winning his fair share of matches, but also falling in defeat at times to some of the other hungry young wrestlers of “The New Generation.”

The competition in the WWF was at an all-time high as the many combatants battled for recognition and title shots. Rad realized he needed some way to thrust himself into the spotlight and get more recognition. Then he met Skip.

Rad was impressed with Skip’s skills. Beyond the flamboyant showmanship of The Bodydonna existed a very talented wrestler who, like Rad, had great confidence in his abilities and wasn’t afraid to pull out all stops to secure a win. Skip needed a partner too.

You see, during the early summer he suffered an embarrassing pinfall loss on national TV to longtime preliminary wrestler Barry Horowitz. Then Skip lost a re-match against Horowitz at one of the biggest shows of the year, SummerSlam

Skip tried to get revenge in a match between Horowitz and Hakushi, but the Bodydonna’s plan backfired.

Instead of causing Horowitz to win lose, Skip’s interference allowed Horowitz to win.

Now Skip had another enemy in Hakushi.

Rad offered to join forces with Skip to help him battle Barry Horowitz and Hakuski. Rad also expressed interest in becoming a Bodydonna. Skip and Sunny agreed to let Rad in on a “trial basis”.

For a few short months, things went well. Together as a tag team, Skip and Rad won numerous matches together and quickly found themselves in contention for a tag team title shot. Rad moved one step closer to becoming a full-fledged Bodydonna when he pinned Barry Horowitz in a singles match, something Skip had never been able to do.

At the 1995 Survivor Series, Rad teamed with Skip, Tom Pritchard and The 1-2-3 Kid (The Bodydonna Team) against Barry Horowitz, Hakushi, Bob Holly and Marty Jannetty (The Underdogs). It should have been the crowning moment of Rad’s career. After seven in a half years in the sport, Rad was finally making his WWF Pay-Per-View debut. Unfortunately, for Radford, the night turned out to be a disaster.

When he first got tagged in, Rad put on quite a show, unleashing a series of suplexes before delivering a spinebuster on his opponent. Then Skip distracted Rad by telling him to do some push-ups. Rad complied with docile obedience. And then, in a reply to what happened to Skip months earlier, Horowitz rolled up Radford for the pin.

The relationship between Rad and Skip got strained even further when a few weeks later the pair lost to WWF tag team champions the Smoking Gunns. However, it had been such a closely fought battle that WWF President Gorilla Monsoon approved Sunny’s petition for a rematch.

Almost from the start of the re-match, things went wrong for Rad and Skip. It ended badly, with Rad being pinned again. Skip and Sunny were beside themselves at not winning the tag team championship. Sunny grabbed the microphone and told Radford he was unworthy of being a Bodydonna and therefore he was fired. She then slapped him across the face. Before Rad could react, Skip clotheslined him from behind and then ran from the ring.

Just two weeks later the former tag partners, Rad and Skip, met in a one-on-one grudge match. Rad was back to his old self, wrestling aggressively, and not getting sidetracked by orders to do push-ups and other silly antics formerly opposed on him by Skip and Sunny.

Radford came running down the aisle, storming the ring and attacking Skip before the bell even rang. A series of hard clotheslines sent Skip sprawling over the top rope. Rad went after his former partner and threw him back in the ring.

After suplexing Skip, Rad performed an elbow drop, but missed his intended target. Skip, confident that Rad was ripe for defeat, headed to the top turnbuckle in preparation for executing a finishing maneuver. However, Rad was faking his injury. Raford intercepted Skip as he climbed to the top turnbuckle. Then Rad proceeded to belly to belly suplex The Bodydonna. Now Rad had Skip just where he wanted him. Radford wore Skip down further with suplexes. From there, Rad whipped his opponent into the ropes and on the rebound, delivered a perfectly executed spinebuster.

Rad went for the cover and the imminent win, but during the chaos the referee got knocked down. Taking advantage of the moment, a near identical version of Skip entered the ring and knocked Rad out. Minutes later, as Skip had his hand held high in victory, Sunny proudly introduced the newest member of The Bodydonnas. His name was Zip, and Sunny informed everyone that Zip was Skip’s brother.

Shortly after this storyline ended, Louie Spicolli was gone from WWF.

THE FINAL RUN

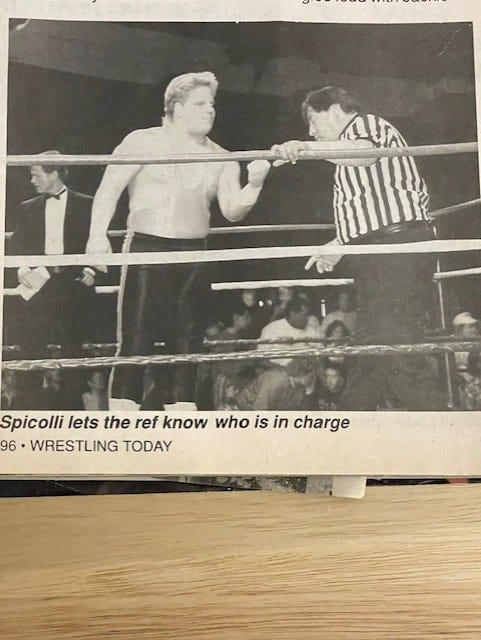

Spicolli’s next stop in 1996 was ECW and he remained there through a portion of 1997. In ECW, he got to show more of his ability in the ring and personality on the mic. The high point was a feud he had with Tommy Dreamer.

In late 1997, Spicolli signed with WCW. After a slow start, he was put into a storyline where he was Scott Hall’s lackey. It was the most high-profile storyline of his career. Spicolli showed a funny side of his personality, and it resonated with the audience and the WCW decision makers behind-the-scenes.

Spicolli’s air-time increased and in storyline he started a feud with Larry Zbyszko, initiated by stealing Zbyszko's golf clubs, bringing them to the ring and destroying them.

This set the stage for a match between Spicolli and Zbyszko at SuperBrawl VII PPV, to be held February 22, 1998.

It appeared Spicolli was poised to get the most significant push of his career.

However, the match never happened.

Louie Spicolli passed away on February 15, 1998.

He was 27 years old.

“My ultimate goal in wrestling is to be looked at with respect,” Louie told me early in his career. “‘Winning’ titles aren’t necessarily the most important thing to me. What counts is when people think of the name Louie Spicolli after I retire, they say, “Hey, he was a good wrestler who left his mark on the sport.”

You can subscribe for free to receive all my new posts. If you like my work, please consider upgrading to a paid subscriber to get exclusive content, like posts about and pictures of wrestling memorabilia from the ‘80s to present from my personal collection.

Listen to my two podcasts, The Pro Wrestling Exuberant and Only The Best Independent Wrestling, for free at https://theprowrestlingexuberant.buzzsprout.com.

You can also follow me on twitter/X at https://x.com/tpwexuberant for more original wrestling content.

I don't need to say that the posts about the humans are the best parts of this newsletter. I think all know that already. This is fantastic though. It's just a shame the ending had to be so abrupt.

In wrestling age, Louie had 20 years left in him at least, which is what makes this story so sad. You never know what he may have been able to do. Considering he was born after Chris Jericho, it's possible he could've been on (or at least at) television tomorrow night on RAW had circumstances been different.

This is much like the last story on Rasta in that the timing was just a little bit off. Being brought into the WWF in the Spring of 1995 is literally the worst time this move could've been made. If something could've changed so that he was brought into WWF in Spring 1996 instead of Spring 1995, maybe Louie could've ridden the wave with the other ECW guys brought in around then (Steve Austin, Mick Foley, etc.). It's also possible that he could've still flamed out, but the heartbreaking part is that we'll just never get to know.

Great job as always!

Good work here! Much like Candido, Spicolli was a very talented guy and deserved much better than the wrestling business gave him.